- Home

- Northrop, Michael

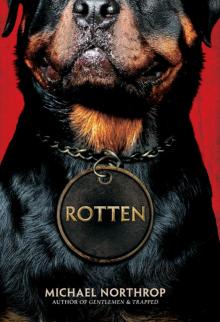

Rotten (9780545495899) Page 2

Rotten (9780545495899) Read online

Page 2

“He’s not weird,” she says, acting offended. “He’s handsome!”

“Jon-Jon the Rottweiler,” I say, and just like that, it comes to me. I put down my empty bowl. “Johnny Rotten,” I say.

Johnny Rotten was the lead singer of the Sex Pistols. They were the first big punk band and pretty much the reason some people still stick safety pins in their noses, ears, or general facial regions. That’s when you know you’re a good band, when you can get people to do stuff like that. I just listen to the music and wear black boots sometimes. Anyway, it’s an awesome name, and I’m kind of proud of myself for thinking of it. Mom’s not convinced.

“Oh, I don’t know,” says Mom. “It sounds so mean.”

“Exactly,” I say. “Have you seen that thing’s teeth?”

She makes a sour expression. “And he wasn’t a very good singer, you know? Not really.”

I don’t like it when Mom talks music with me. It’s annoying. And anyway, I think the Sex Pistols are really good: “I am an Antichrist / I am an anarchist!” It’s like those are practically the same word, but they mean completely different things. I like that kind of stuff. All the tests say I’m more “verbal.”

“Well, that’s perfect, then,” I say. “Because I don’t think this dog can sing, either.”

Mom tries to keep the frown on her face, but the corners of her mouth tip up and she smiles.

The good mood lasts until I get up and head toward the door.

“Going to see Rudy,” I say. My voice is like I’m apologizing.

“Mm-hmm,” says Mom, not really looking at me.

It feels like there should be something more, but there’s not. Mom may not want me to hang out with my friends, to go back to all of that, but what’s the alternative, locking myself in the basement? I push through the front door and let the warm, bright air smack me in the face. Halfway across the front lawn, I pull out my phone and reread Rudy’s last text. He’s downtown already, probably out behind the CVS. I type with one hand: On my way m/

I have to walk. One of the great indignities of being away all summer is that my learner’s permit hasn’t had a chance to emerge from its cocoon as a license. I’m in the bike lane, and a green minivan blows by me, doing about sixty and kicking up a plume of dust and dirt. A little chunk of something, a pebble maybe, whizzes past my head. I hear another car coming and take a few steps up onto the Franciscos’ lawn until it passes.

The CVS is the center of things downtown, the only recognizable brand we’ve got now that the Subway closed. I stop and look around once I reach it. I’m half looking for Rudy and half checking to see if there’s anything new in town. The verdict: Rudy’s not there, and there’s never anything new around here.

This town excels at the old, though. As if to prove the point, Mr. Jesperson bangs through the front door of the CVS with a copy of the Stanton Standard under one arm and a CVS bag in one hand. The bag looks ready to burst, and I figure it must contain all the pills he has to take to continue to function at his age.

“Jimmer!” he says, spotting me as we head toward each other on the walkway.

“Hi, Mr. J.,” I say. I’ve always called him that, because when I first met him, I was too young to manage Jesperson.

“Where you been?” he says. “Haven’t seen you around hardly at all.”

I can feel my eyes narrow, and for a second I think maybe he’s screwing with me, like he knows exactly where I’ve been and he’s just making me say it. But then I get a grip. Mr. J. isn’t giving me a hard time. He hasn’t given me trouble even once in his very long life. But he’s looking at me, waiting for an answer.

“Aw, you know,” I say. “I am a man of mystery.”

That’s either good enough for him or he realizes that’s all he’s going to get. He looks down and begins rummaging through the overstuffed bag in his hand. Oh no, I think. Please, for the love of all that is not impossibly lame, no. But, yes, he’s searching through his bag for candy. He’s going to give me candy, like I’m still five years old and can’t say his name. And he’s going to do it right here on this walkway in the absolute center of town. I look around to see if anyone is coming, and of course they are. The sidewalks are getting busier. There’s a stream of dressed-up families emptying out of the church at the end of the block.

It takes him forever. Even when he finds the little plastic bag of candy, he still has to open it. I watch the veins shift and the liver spots stretch as he maneuvers the bag and pinches its top. People are passing us on either side, nodding at Jesperson, who they all know and trust. I’m sure they wonder why he’s wasting his time on me.

“That’s OK,” I say. “Really.”

“No, no,” he says. “You always loved these things.”

They’re butterscotch hard candies. They’re one of those old people’s candies, like gumdrops, but it’s true, I loved them — when I was five.

“Can I …” I start, but it doesn’t seem like I should say “help,” for some reason. “Do you want me to …”

Finally, the bag pops open — and he gives me one piece! All that, and I get one piece. I mean, I don’t like them as much as I used to, but all that for one butterscotch?

“Thanks,” I say, more for the effort than the candy. His face is red from wrestling with the bag, and I imagine him sitting alone later, dentures out and slowly chain-sucking the rest of the butterscotches to death.

Normally I’d walk through the CVS now. That’s where I was headed, but I feel like I’ve interacted with the general population enough at this point, so I turn and walk around the side of the building. Sure enough, there’s Rudy Binsen, my best friend since forever. He’s wearing a T-shirt that says HANG OUT WITH YOUR WANG OUT and sitting on the old, beat-up bench, on the side farthest from the garbage can.

“What’re you eating?” he says when he sees me.

“Butterscotch,” I say.

So that’s it, the first words we’ve said to each other all summer. I sit down on the bench, not too close to him but not too far away either, because there are four or five bees buzzing around the top of the garbage can on this side.

“Geez, man,” says Rudy. “It’s been forever.”

“Seriously,” I say. I look over at him. “Nice shirt. Solid advice.”

Shirts like that are kind of his thing, but I haven’t seen this one before.

“Wearing my Sunday best,” he says. “So how was ‘upstate’?”

He actually makes the air quotes with his fingers. I ignore them.

“OK,” I say. “Boring.”

“Yeah, right. Because you were ‘at your aunt’s house’ or whatever?”

He doesn’t make the air quotes this time, but I can hear them.

“Yeah,” I say, trying to sound casual.

“Dude, that’s ridiculous. They don’t ‘send you to the country’ when you already live in the middle of nowhere.”

I look up at the sky. It took, what, thirty seconds for us to get into this again? “Yeah,” I say, “but this was, like, the turbosticks: no Internet — my aunt doesn’t even have a cell phone.”

“Yeah, more like everyone up there is in a cell,” he says, then laughs at his own joke.

“Mom thought it would be good for me,” I say. “Get me away from all the bad influences around here.”

He makes a fake wounded expression, like I’ve hurt his feelings.

“You seen Janie?” he asks after a while.

Perfect, I think, the only topic more uncomfortable than the last one.

“Nah,” I say. I want to stop there, but I can’t help myself. “Is she, you know? Is there someone …”

“You mean someone else?” he says.

“Dude, man, I don’t even know,” I say. “I don’t know if ‘someone else’ really enters into it at this point. I just mean, is she, like, seeing anyone?”

Rudy looks over at me for a second. I know him, so I know that he’s thinking about making a joke, maybe something about �

��entering into it.” But he thinks better of it, because he knows me, too. “I don’t think so,” he says, shrugging. “And I haven’t seen anything online.”

“Yeah, OK,” I say. I’m sort of wondering if that means he was checking out her profile, but I guess he might mean in his news feed. We all have “mutual friends,” even if we don’t necessarily like them. “I just thought you might’ve heard something.”

“Nope,” says Rudy. “You should just call her or something.”

Which is obviously true, but I haven’t yet. The last time we talked, it didn’t go so well. Which is like driving a car into a train and calling it a wrong turn. “Yeah,” I say. “Hey, speaking of all that” — I wave my hand around to show that I’m talking about more than one person now — “I haven’t updated my status or anything. So don’t tell anyone I’m back yet, OK? I need to get my bearings or whatever.”

“Well, that’s too bad,” says Rudy. “Because it’s too late.”

“Who’d you tell?” I say.

“Mars,” he says, holding up his phone. “Right before you got here.”

“Yeah, Mars.” That’s Dominic DiMartino. “So Aaron will know, too.”

“Yeah, probably. What’s the big deal? Those guys are cool. You know, usually.”

“Yeah, yeah, course,” I say.

“I’ve been hanging with them a lot,” he says. “Not like you’ve been around.”

“Yeah, yeah, I know. It’s cool.”

“Well, I don’t know why you’re being a freak, but I think we’re supposed to head over to Brantley tomorrow. You in?”

“Not sure I can handle the excitement,” I say.

“Seriously, man …”

“Yeah … Course … What time?”

“Don’t know … I’ll text you.”

“Cool, cool,” I say.

We just talk for a while after that, and he catches me up on some of the nothing that happened around here. We roam around downtown a little, because there’s only a little of it to roam around. Then I tell him I have to go.

“Sure, man,” he says.

“It’s good to see you, man.”

“Yeah, you, too.”

And it is good to see him. It’s good to talk to him, and I sort of feel like he let me off the hook easy and we’re pretty much back to normal. So that’s all good, but I feel uneasy and on edge as I head back home. Brantley tomorrow, with all of them … It’s like I haven’t been gone at all.

I guess that’s the problem.

I walk home the back way, along the bike path through the woods. It’s quieter, and you don’t feel like as much of a second-class citizen as you do walking along the side of the road. About halfway, there’s a tree that sort of leans out into the path. It’s bent like an elbow, and when I was a little kid, I had to jump to touch the part where it bends. Today, I just reach my hand out and slap it as I pass. It’s a tradition.

Walking that way, I come home by the backyard. Even before I get there, I can see that the fence has been patched up. You can still see the old holes through the new wire, and I wonder why Mom had it done. Then I notice that the grass is a lot longer than usual, and I suddenly realize what it’s hiding. Mom must let the dog do his business out here.

The grass is like eight or ten inches high in the center and slopes down to a few bare patches near the posts. The fence is barely waist high, and normally I’d hop it and go in the back door. But I just walk by. The grass has been mined, and the corners have been dug up and pissed to death.

I walk around and go in the front door. I’m a little distracted, thinking about a few things that Rudy said and about that trip to Brantley tomorrow, but I sort of snap back to reality as I turn the door handle. I remember the big, barking commotion last night. I push the door open anyway because, you know, I live here. There are two quick barks, but that’s it. As soon as he sees who it is, he turns and starts slinking back out of the kitchen. Just to test something, I say: “What up, dog?”

As I suspected, it just makes him slink faster. Once he’s gone, I realize I forgot to tell Rudy about this dog. I’m not sure why. Nervous, I guess. It’s not like I had any other news to share — and he’d at least appreciate the name. He was a big fan of my last pet, that dead frog, Mr. Hops, croaked on a Thursday. RIP, little fella: Rot in Place.

As I’m heading toward the front room, I can hear Mom coming down the stairs. Maybe she was just up there getting the laundry, I tell myself, but it’s also possible she was going through my stuff. She makes it up to me later by bringing in pizza rolls while I’m camped out on the couch, watching preseason football.

“What is it, a holiday?” I say, sitting up to take the plate.

She bats me on the head. “Careful,” she says. “They’re hot.”

“OK,” I say, moving my head from side to side to point out that she’s in between me and the TV. It’s Texans versus Rams, so I don’t have a rooting interest, but it’s a pretty good game, and the front room is sort of my territory. At least that’s the way I see it. She’s still standing there. For a second, I think: Uh-oh, she found something in my stuff. But then I remember there wasn’t anything in my stuff. Finally, I figure it out.

“Thanks, Mom,” I say.

“You’re welcome, baby bird,” she says, and turns and walks away.

If anyone else called me that, I would literally, physically kill them. With a dull spoon. As it is, I reach for a pizza roll.

“Hot!” she says as she exits the room, her back still to me.

I have no idea how she does that, but I drop it back on the plate. It didn’t feel too hot, but it’s the insides that’ll get you with those things, so I watch the game for a while. A few minutes later, I grab a pizza roll and pop it in my mouth. It’s just the right temperature: warm but not blistering. When I look back up, I see the dog looking at me.

Once again, it’s just his head. He’s in the hall, kind of poking his face into the room. I feel like telling him to man up — or dog up, maybe — but he’s built more solidly than half the guys the Rams are currently trotting out on defense, so I guess I should be careful what I wish for. As it turns out, he’s not looking at me after all.

I follow his eyes and he’s staring at the plate. The way he hopped around for those biscuits this morning, I should’ve known. “You’re a real chowhound, huh?” I say. This time, he doesn’t slink away. He turns his head a little, sort of dipping his left ear toward the floor, and looks at me. The little brown dot above each eye makes him look like he’s thinking about something much more profound than processed, microwaved food.

“You want a pizza roll?” I ask. “Are you even allowed?”

He doesn’t answer, but he tips his head back the other way — right ear toward the floor — when I say “pizza roll,” so I think he was at least able to identify the noun. I heard somewhere that chocolate is bad for dogs, but I’m not sure about the rest of the vast kingdom of junk food.

He takes two small steps forward. Now his shoulders are in the room. I raise my hand and he takes a step back, but he stops once he sees that I’m just reaching for the plate. I hear something happen on the TV — a Texan touchdown, probably — but I don’t look. I feel like if I look away, he’ll vanish.

Instead, I hold up a pizza roll, and he very slowly, very cautiously takes a few more steps forward. He’s all the way in the room now, and I’m pretty sure that, food or not, that’s as close as he’s going to come. I flick my wrist and toss the little tan roll to him. Just like with the biscuit, he rises up on his hind legs and snatches it out of the air. He catches it in the side of his mouth. He’s already chewing by the time he lands, but a pizza roll being what it is, a glob of red filling pops out the side and lands on the floor.

He finishes gobbling down the roll and looks down at the filling, ears up, legitimately surprised. I don’t think he’s ever eaten something with filling before. He must be a quick learner, though, because he dips his head down and licks it up in three quick

swipes of his tongue. He raises his head up and looks tremendously pleased with this whole turn of events.

Then he looks at me and starts making that weird noise in the back of his throat. I toss him another one. Once again, he Air Jaws it. This time, no filling escapes, but he still looks around for it when he’s done. Maybe he’s not as fast a learner as I thought. While he’s sniffing the floor, I pop the last one in my mouth.

“You snooze, you lose, boy,” I say.

I hold up my hands to show him that they’re empty.

“No more,” I say. “You cleaned me out.”

He looks at my hands, looks at the plate, then turns and walks out of the room. He doesn’t even say thank you.

After the game’s over, I pick up my phone and go looking for the dog. I find him in the living room. The living room is also the dining room because it’s just off the kitchen and the house isn’t that big anyway. JR has staked out a spot in the corner. His eyes follow me, but he doesn’t move one way or the other. I point my phone at him. “Pizza roll,” I say.

He looks up and I snap a picture. I head back to the front room and send the pic and a quick text message to Rudy: Forgot 2 tell u, got a dog. Name is Johnny Rotten & looks like this.

I get a text back: Rawk! m/

A few minutes after that, he sends another one: Must meet dog. Maybe start band?

I think that’s pretty funny. Can you imagine?

No problem, I type. I figure there’s already enough going on tomorrow, so I add: Tuesday?

Rudy’s reply is just m/ — the devil horns always mean yes. I didn’t mention that the dog is completely neurotic, but I guess he can find that out for himself.

It’s Monday. In a week, Mondays will suck because of school. Today might suck too, but that will be self-inflicted.

Mom has already left for work by the time I get up. I stumble around the empty kitchen, and I can tell what she had for breakfast by the dishes in the sink. It always sort of reminds me of a zombie movie: the house empty, but with signs that people had been there recently (“This toaster is still warm!”). I sit there eating my cereal and start to wonder where the dog is.

Rotten (9780545495899)

Rotten (9780545495899)