- Home

- Northrop, Michael

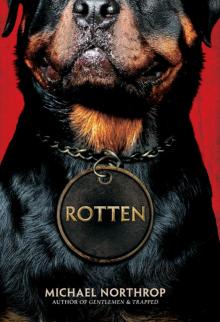

Rotten (9780545495899) Page 8

Rotten (9780545495899) Read online

Page 8

“Well, while you’re waiting,” he says.

He steps back toward the door.

“Don’t open it all the way,” I say, because JR is still in the room.

He opens the door just enough to wedge his body through. JR watches it open, but he doesn’t make a break for it. And just like that, Rudy’s back. Even before he pulls his left arm back inside, I can tell there’s something in it. It’s a little fishing pole, like the cheap plastic kind that every kid around here had at one time or other. I had one, but it broke. Because it was cheap and plastic.

“I found it in the stockroom!” he says.

“Do they sell those at the market?” I say.

“Well, they did at some point.”

“And you went to work wearing that shirt?”

“Yeah, why not? I was just working in the back.”

“Yeah, that one’s actually kind of appropriate for ‘working in the back,’” I say. “Does that thing have a hook and stuff?”

“Yeah, it’s fully functional,” he says. “You still have yours?”

“My hook?” I say, trying to trick him into saying “your pole.”

He’s too smart, though, or at least too experienced with sexual innuendo.

“You know what I mean,” he says.

“Yeah,” I say, “but I don’t have any of that stuff anymore.”

“Well,” he says, looking down at the pole. “We got one hook….”

“Wouldn’t be any trouble to find a few night crawlers after all the rain yesterday….”

“You want to?”

“Yeah, sure,” I say. “What d’you think, just down to the pond?”

“Yeah, why not?”

“Because we’re not eight anymore, and there’s no way we’ll catch anything worthwhile with that thing,” I say. “It’s a frickin’ toy.”

“Nice day, though,” he says.

He’s right about that.

“OK, let’s go.”

“Think we should take Killer here?”

JR is still looking at the edge of the door, where it used to be open.

“Sure,” I say. “I’ve already taken him that far a few times. But we should probably stop calling him that, you know, all things considered.”

Rudy looks at me.

“Public relations — image matters,” I say. I saw that on a folder Mom brought home once. It’s the sort of phrase that is obviously true but also makes you never want to work in an office in your life.

“Public Image Limited,” says Rudy.

“Much better,” I say.

PiL is Johnny Rotten’s band after the Sex Pistols.

“Anger is an energy,” says Rudy. It’s a line from “Rise,” one of their best songs.

“You could be right,” I say, another line from it.

The good thing about getting into these bands way late is that you really only have to listen to their best stuff. I listen to some new bands, too, but they keep letting me down and going mainstream. Anyway, it’s kind of a cool exchange.

And then we head out to go fishing with one hook, a kid’s toy, a dog on a bright blue leash, and the beginnings of something like a plan.

“We can call Mars from there.”

“Well, ain’t we a couple o’ rednecks?” says Rudy as we walk along the bike path behind town, heading toward the pond. JR isn’t paying much attention to either of us. His world is at the end of his leash, and his senses are working overtime as he sorts through the sights and sounds and smells.

“Yeah, right?” I say. “We goin’ down the crick, do us some fishin’!”

We make fun of it, but we keep walking straight there. We’re quiet for a while, and I try to concentrate on what I’m doing. I stay even with JR and don’t let him tug on his leash too much, and I stand up straight and don’t make any sudden movements.

“You look like you have a stick up your butt,” says Rudy.

“I’m working on my ‘calm, assertive energy,’” I tell him.

“Your what?”

“I’ve been watching a lot of Dog Whisperer reruns,” I say.

“Oh right,” he says. “The timeless wisdom of basic cable. What’s that guy’s name again?”

“Cesar Millan,” I say.

“Right. You still look like you’ve got a stick up your butt.”

“Maybe I do.”

Ten minutes later, we’re at the pond. It’s small, shallow, and choked with vegetation. “Well,” I say. “We have an excellent chance of catching some really primo weeds in there.”

“Yeah,” says Rudy, looking down at the little fishing pole in his hand. “There’s about a one hundred percent chance we’re going to lose this hook.”

“Well,” I say, “let’s at least kill a worm first.”

Before I can start turning over rocks and pawing around for night crawlers, I have to figure out what to do with JR. As soon as we stopped, he turned around, figuring we were heading back from here, like we’d done before. It was one of those weird moments of dog intelligence that sort of catches you off guard. Or it caught me off guard anyway. We aren’t heading back, though, so now he’s just watching us talk and looking down the slope at the pond.

I look down the slope, too. There’s a stubby, half-drowned tree jutting out of the bank and leaning over the water. “Why don’t we go down there, and I’ll tie the leash up to the tree?”

“What,” says Rudy, “you think he’d run away?”

“Well, not from us, I don’t think,” I say. “I mean, not like a jailbreak, but if he sees a chipmunk or something, we’ll never see him again.”

“Or it,” says Rudy.

“Yeah, right?”

We head down the slope. JR is like, All right, let’s go there. He takes the lead, pulling on the leash in a way that I’m pretty sure is going to result in me rolling most of the way down. I lean way back instead, and when he stops at the bottom, I fall on my butt.

“Smooth,” says Rudy, as JR begins slurping up pond water.

I wait for him to stop and then loop his leash around the trunk of the little tree. He watches me do it, realizes he isn’t going anywhere, and lies down. Meanwhile, I go about the not especially difficult work of finding a good, fat worm.

“Man,” I say, slowly working a five-incher out of the dirt. “This place is crawling with ’em.”

“That’s what you like to hear,” says Rudy. “Pond-side views, crawling with worms, must see!”

“You’re going to end up just like them,” I say, meaning his parents.

He strikes a superhero pose and points his finger at the sky. “Never!”

“You’ve got the real-estate gene on both sides.”

“They can fix that now,” he says. “Nanosurgery.”

“Nope, you’re inoperable. Might as well add your name to the sign: M&S&R Realty.”

“Don’t even say that, man. That is just … I will drown myself right here in this pond.”

“I’ll help.”

He laughs. “Nice,” he says. “Let’s catch some fish.”

“All right,” I say. “Give me the pole.”

“Does that line work for you?”

“Yeah, ha-ha. Seriously, I’ve got a thick five-incher here that needs it bad.”

“That’s sad,” he says. “I’m holding a three-foot rod that — Oh, wait, should we call Mars first?”

“Oh yeah,” I say. My good mood goes out like a light, and I toss the worm into the grass halfway up the bank, a last-second pardon. “Yeah, let’s.”

Rudy takes out his phone. “Why are we doing this, exactly?”

“Dude, they’re going to make my mom pay for the hospital and who knows what else,” I say. I don’t tell him the other thing I’m worried about. It sort of seems like saying it would make it more real, and I’d like to keep that thought firmly in the realm of paranoid delusion.

“I thought you said it wasn’t that bad?”

“It isn’t, but you know him — hi

s whole family.”

“Oh right,” he says. “Definitely don’t want to give them a blank check.”

“At all. Mom is pretty stressed about that stuff already.”

“What stuff?”

“Money stuff. Her office is The Suck right now.”

“Oh,” he says. “Got it.”

“I just want to get him on record as still having all his fingers and not suffering ‘emotional distress’ or whatever they’re going to try to bill us for.”

“He’s not going to say anything like that,” says Rudy. “Since when has Mars ever talked about his emotions?”

“Yeah, I know,” I say. “But if he just says he’s OK or it’s no big deal or something like that, that’s a good start.”

“Yeah,” says Rudy. “I could see him doing that…. You just want, like, confirmation of his OK-ness. So, call or text?”

“Let’s call. You’re, like, my witness. Maybe you can get him talking.”

“OK,” he says. “I’ll put it on speaker.”

“Cool,” I say. I turn to JR and make the shush sign, which there’s a decent chance he’ll understand. The last thing we need is him barking at Mars’s voice and giving us away, but he’s conked out already. He’s lying on his side and soaking up the sunlight in his black fur like a big, drooling solar cell.

Rudy hits speaker. The air is warm and still and I can hear the ringing pretty clearly. Once, twice, three times, and just when I’m expecting it to go to voice mail, Mars picks up.

“Hey, jerk-off,” he says to Rudy, who pulls the phone closer to his head to talk.

Rudy’s response is less polite, and once the formalities are out of the way, he gets right down to business. “How’s the mitt, man?”

There’s a long pause. Just say it’s fine and get this over with, I think.

“I don’t know,” Mars says. His voice sounds small and far away over the speaker. I kick the dirt and Rudy looks over at me. JR raises his head.

“God, just grow a pair,” says Rudy. For a second, I think he’s talking to me.

“Easy for you to say,” says Mars. “Dog practically ripped my hand off.”

I form the words “that’s bull” slowly, so that Rudy can see them.

“Exaggerate much?” he says into the phone.

“Whatever,” says Mars. “My mom says it’ll probably get infected.”

“Yeah, right,” I mouth.

“Your mom?” says Rudy. “What about the doctor?”

Rudy has a point. Mars’s mom is basically the opposite of a doctor: uneducated and harmful. Mars doesn’t answer, so Rudy tries again. “I hear it wasn’t really that bad.”

It wasn’t, I’m thinking. And he hopped the fence and provoked it.

“Yeah,” says Mars. “Where’d you hear that, Jimmer?”

“Could be,” says Rudy.

“Yeah, well, who’s gonna believe him?” says Mars.

And there it is. Rudy looks over at me and grimaces: He’s got you there.

Mars is still going: “Maybe we should ask his ‘aunt’….”

“Yeah, yeah,” says Rudy.

“Hey, where are you right now?” says Mars.

“On the couch,” says Rudy, looking out at the pond.

“Why don’t I come over and play some Kinect?” says Mars.

“You up to it?” says Rudy. There’s a splash farther down the shore, some turtle or duck or something. Rudy covers the phone with his other hand, but it’s too late. I don’t know if Mars heard, but he’s quiet for a few seconds.

“I can beat you with one hand,” he says, finally. But he sounds different now, more cautious. Stupid turtle.

“Nah, Xbox’s broken,” Rudy says. “Anyway, I got some stuff to do. Just wanted to check in.”

“Yeah,” says Mars. “All right. Check ya later.”

“All right,” Rudy says. He hangs up.

“Dammit,” I say.

“Yeah,” says Rudy. “He’s pretty smart, for an idiot.”

“That’s such bull,” I say. “All of it.”

I kick the ground again, harder this time. The first worm has made its escape, so I find another one.

“You know,” says Rudy as he impales the night crawler on the hook, folds it back, and skewers it again. “If there’s anything you want to tell me about this summer, this might be a good time.”

I make a screw-you-very-much face, but I’m actually thinking about it. And then, just like that, he casts the line out into the pond. The red-and-white plastic bobber lands with a little splash. JR gets up to investigate as Rudy and I sit down to start watching it. After about fifteen minutes without even a nibble, he hands me the pole and it’s my turn to “fish.”

I’ve got a bite!

As soon as I start reeling it in, I can feel it’s not much. Probably just a dumb sunfish, the annoying bait stealers that have always been the enemy of any worthwhile fishing around here. Still, it’s been years since I’ve reeled anything in and it’s sort of fun.

“Lucky!” says Rudy.

He just handed me the pole a few minutes ago, and the timing and the fact that he is so obviously jealous make this even more fun. The little fish comes into view as I pull it closer to the surface, but it’s hard to see it clearly because of the ripples the line is causing. Finally, I tug it out of the pond, and we can see it flapping around on the end of the line.

“Sunfish,” says Rudy. “Nothing.”

JR disagrees. He’s been moving around over by his tree, and now that the little fish is out of the water, I risk a look back. He’s at the end of his leash, staring at the fish. His mouth is hanging open and as he snaps it shut to start barking, a thick lasso of drool slips off and flies through the air. Rudy sees it, too.

“I think he’s hungry,” he says.

“He’s always hungry,” I say.

JR barks at the fish a few more times as I raise the pole and swing it toward me, but once I grip the thing in my hand and start trying to work the hook out, JR’s mouth shuts and his eyes get wider than I’ve ever seen them.

“Hey, dude,” says Rudy. “Eyes on the prize.”

We only have one hook, so I concentrate on working it free. It’s not in deep. The little fish is slick in my hand but it’s not as cold as I expected. It must’ve been in the warm water near the surface. It fits easily in my hand, so keeping it still isn’t a problem like it was when I was seven and trying to wrestle with a trout. The hook pops out.

As I swing my hand back to toss the thing into the pond, I hear JR’s leash tearing the bark off the tree. I turn around just to make sure he hasn’t pulled the whole thing up by its roots. He looks at me, looks at the fish, looks at me.

“Do it,” says Rudy. “Seriously.”

Now, the thing to do with sunfish is throw them back. They’re too small to keep and too bony anyway. But I guess that’s human thinking.

“Really?” I say.

“Yeah,” says Rudy. “Why not?”

I look around like there might be a game warden watching us from behind a tree.

“I don’t know,” I say. I feel the fish in my hand, still trying to flap and slap its way to freedom. “Kind of cruel.”

“To what, the fish?” says Rudy. “Is there any species that’s ever been treated worse? And anyway, look at your dog. It’s kind of cruel to show him this fish and then just throw it back.”

I picture JR, his look of confusion as the fish splashes back into the pond and disappears, confusion and then profound dog sorrow. What the heck. I turn and deliver the fish with a short, underhand toss. He gathers his back legs underneath him, like he does for a biscuit, but he’s still leashed to the tree.

“Nononono!” I say, but it’s too late.

He launches himself into the air. His jaws snap down on the fish in midair, a split second before he reaches the end of his leash.

The fish is like: Freedom! Dog! Arrrr!

JR is like: Fish! Leash! Yoink!

He’s

yanked backward — I hear the tree creak from his weight — and he crashes back to the ground. But his jaws never stop working. He’s literally chewing as he falls. By the time he stands back up again, he’s licking his lips. His thick pink tongue swipes out and over, looking for any last traces of fish.

“Whoa!” I say.

“He obliterated that thing,” says Rudy, and his tone is just pure awe.

“Well,” I say, reviewing my decision. “I don’t think it suffered.”

“That was the coolest thing,” says Rudy. “Maybe ever.”

I can’t think of anything to add, so I don’t.

“All right,” says Rudy after a while. “My turn.”

“Fine,” I say. “You go find a worm.”

“No problem. This place is crawling with them.”

A few minutes later, JR is lying down in the sun again for some solar-powered digestion, and Rudy is settling in for what I expect to be a long turn with the fishing pole. I’m just watching the water, checking my phone, watching the water, scratching my neck, watching the water, swatting a mosquito, scratching the bite, checking my phone.

“I think I got —” says Rudy.

I sit up.

“Nothing.”

I slouch back down. The sun feels good on my face. It looks like I’ll get some color this summer after all.

“Not a bad Friday,” says Rudy.

“Not at all, especially considering it’s our last one.” School starts Monday.

“Dude, don’t even talk about that. Seriously. I’m not ready.”

“You and me both,” I say.

Just the thought of those hallways, those people, the crowds in between classes, and the smell of whatever it is they use to semi-clean the place … It makes my stomach want to implode.

“OK, let’s settle this,” says Rudy. “Neither of us talks about Monday until Monday.”

“Deal,” I say. “Except I’m going to need a ride.”

“OK, starting now,” he says. “Yeah, I figured you would. OK. Now.”

I make a lip-zipping motion with my right hand. It feels a little stiff with fish slime, so I wipe it on my jeans again. A few minutes later, we hear people up on the path, heading our way. We both sort of straighten up, and JR gets to his feet. If it’s anyone we know, Rudy will probably start acting like this is all a big joke, waving the pole around like he’s trying to break it. And I’ll probably act like I just stumbled across this impossibly lame scene. But it’s not anyone we know, not really, anyway.

Rotten (9780545495899)

Rotten (9780545495899)